Mastering Authentic Writing: Best Online Courses

Essay? Commentary? Creative Non-fiction? Short Story?

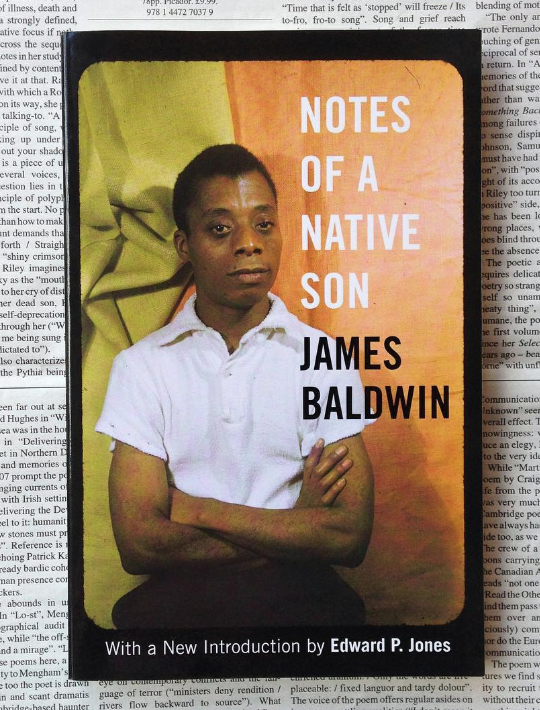

What is this piece of writing by James Baldwin, and how do we, as creative writers, approach it intelligently and thus learn from it?

To get the most from this discussion, I suggest you read first (click here) and give some thought to how Notes of a Native Son hits you. This initial reaction is crucial and deeply personal. Making a few notes about that reaction also allows you to be fully authentic in your experience, which frankly, is the point of reading. A writer may have a particular agenda or want you to feel a certain way when reading their work, but once you are alone and investing your energy into a story, you are in a place of complete freedom. What comes to you as a result of that reading isn’t right or wrong. It simply “is,” and often it’s profoundly personal and impossible to articulate, or if you wanted to articulate what you felt or experienced, you might feel…strange. So, don’t say anything to anyone upon your first read. Experience the writing, the writer, and the story. Make a few notes to yourself, and don’t fret about “getting it” or not; that you read it is all that is required. Opinions and conclusions come later (if at all).

Here at the Studio, we took on Balwin’s Notes as our opening gambit back in September. Welcome back to school! And met a meaty piece of writing, twenty-seven pages long, that was largely expository in presentation

.

Expository writing, as the term implies, exposes the author’s thoughts or experiences for the reader; it summarizes, generally, with little or no sensory detail. Expository writing compresses time: For five years I lived in Alaska. It presents a compact summation of an experience with no effort to re-create the experience for the person reading.

~ Tell It Slant by Brenda Miller and Suzanna Paola, 2nd Ed.

Notes opens with a series of “attack” sentences–as defined by Gordon Lish and can be read about more in this essay by Jason Lucarelli–and each works to “throw” down what the whole piece is about but not through direct and apparent means. “Your attack sentence is a provoking sentence,” Gordon Lish taught. “You follow it with a series of provoking sentences.”

See how Baldwin does this attack by staying quite close to the subject at hand and the time of his topic (the setting/situation):

On the 29th of July, in 1943, my father died. On the same day, a few hours later, his last child was born. Over a month before this, while all our energies were concentrated in waiting for these events, there had been, in Detroit, one of the bloodiest race riots of the century. A few hours after my father’s funeral, a race riot broke out in Harlem while he lay in state in the undertaker’s chapel. On the morning of the 3rd of August, we drove my father to the graveyard through a wilderness of smashed plate glass.

The day of my father’s funeral had also been my nineteenth birthday. As we drove him to the graveyard, the spoils of injustice, anarchy, discontent, and hatred were all around us.

We now know the story is about father, death, birth, continuation, and riots (externally and internally). The riot aspect of the story is that outer/inner arc material and the reader will never be fully freed from the fact of “riot.” Riot in relationship, riot within a man’s soul and mind, riot in the country, riot within a family, and a riot with God.

Yet, there is a quality of telling in Notes that never gives way. In fact, you must read ten pages before the first true scene appears.

A scene is a moment in time when something happens to move the story forward. ~ The Studio Scene Recipe Card

Because we wait until page ten for our first scene, there is a restlessness in the modern reader (this story came out in 1955, or near about) who is used to instantaneous hits of info and twenty-minute blasts of drama. In class, we learned that scene is “best” primarily because the reader can better be “in” the story rather than controlled by the writer and their thinking process. As a reader, I wondered, “Where is he going to land? What exactly does he want me to feel of this experience?”

The answer to my question arrives when Baldwin recounts a moment before his father’s death, where he (Baldwin) is denied service in a restaurant because he is black. The rage his father had long been possessed by, the lack of trust of whites, the conviction that nothing would change for the black man–not really–was not understandable to Baldwin until this moment when he, too, finds himself possessed with a consuming (and justifiable) fury that, rather than diminish, increases (like a riot).

“At their best, scenes allow us to enter the action, feel the emotions of the characters, empathize, and even to enjoy catharsis. They grab our attention and let us know that what is being conveyed matters,” Laurie Alberts writes in Showing vs. Telling, a Writer’s Digest book. And that becomes our writerly task then. We get to ask, again and again, where do I want the reader to enter the action and feel? What are the key moments?

For Baldwin, who provides the reader with only eight scenes in twenty-seven pages (and a couple of those are flashback scenes), I wonder if he wanted to control the experience for the reader or perhaps keep the reader away from a fuller experience as a way of keeping them at an arm’s length. Did Baldwin, whose long-suffering as a black man in an oppressive culture, want to honor his experience in the one way he could artistically, which was to deny another access to it? I’m not sure, but when I thought about Notes of Native Son and then thought about the oppressive experiences in my own life as a woman in a culture that does little to honor women or my offspring, I felt a deep and tender respect for his artistic choices. Some things are too personal. Too sacred. Too impossible to speak (or write). Nor does a reader deserve access to some of these unique, sacred, impossible experiences. I don’t know. I’m simply pondering here. But once considered in this way, my restlessness vanished, replaced by artistic respect.

What is Notes of a Native Son?

On the surface, Notes is an essay, but what kind? Personal, literary or new journalism, nature, meditative, the essay of ideas, the sketch or portrait, humor, braided?

The criteria for all of these are the same in that there is a sense of forward movement. The writer is taking the reader somewhere and there is a sense of being moved forward along a line. According to Brenda Miller’s Tell it Slant, some essays can work like a short story and focus on more literary elements like scene, structure, and plot, while others are driven by the writer’s interior voice. In the case of Notes, then, we have the latter. Notes of a Native Son, driven by the interiority of Baldwin’s thoughts, isn’t commentary, nor is it committing the sin of keeping the reader far away due to a lack of scenes. Rather, on the spectrum of the personal essay, is it simply at the far end of offering the reader access to that interior voice. So, the answer is that it is a personal essay.