Best Novel Writing Courses to Help You Craft a Bestselling Novel

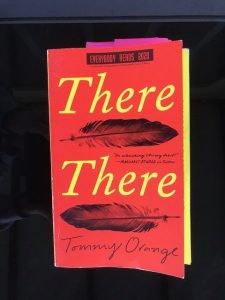

Tommy Orange, author of There, There

We’ve wrapped three weeks on this book, and I’ve taught nine classes with about thirty writers, examining the novel from nearly every craft perspective possible: Plot, voice, POV, and structure while asking through teacherly questions like: Can we find a hero in a book with twelve characters? Can we find a plot from the deck of plots we study? Is there a structure that adheres to the three part form?

But this was also a teaching that needed to stretch us beyond our usual course of analysis and dig into ourselves as members of a society who have benefitted from the genocide of the Native people of this land.

Our time together was of such potency and power, I decided to write up a few thoughts.

History and Accountability

Tommy Orange, through his tremendous gift as a writer, held up a mirror and said, “This is the story of concentrated and focused genocide.” We knew this, of course, we’ve always known this, but his remarkable method of “on the body” and “voice driven narrative” drove the lessons in that much deeper. It doesn’t help that this has been a particularly brutal year of hard lessons. Many of us are terrified of each other and possible contagion, divided against one another too, and also reckoning with the reality of ecological devastation with species going extinct, fertility rates dropping, cancer deaths rising, and poisoned land and waterways. We are learning to face that in these two hundred and forty five short years of “democracy” which has been a cover for an extraction-of-resources-no matter-the-cost-and-make-as-much-money-as-possible policy now leaves this bounteous land teetering. We’ve not only destroyed the luminous Native people, broken their families, homes, and hopes, but we’ve also sneered at their thousands upon thousands of years of intelligence of how to live with the land in harmony, dignity, and respect. What have we done?

Tommy Orange tells us, vividly and without holding back:

“They did more than kill us. They tore us up. Mutilated us. Broke our fingers to take our rings, cut off our ears to take our silver, scalped us for our hair. We hid in the hollows of tree trunks, buried ourselves in sand by the riverbank. That same sand ran red with blood. They tore unborn babies out of bellies, took what we intended to be, our children before they were children, babies before they were babies, they ripped them out of our bellies. They broke soft baby heads against trees. They took our body parts as trophies and displayed them on a stage in downtown Denver. Colonel Chivington danced with dismembered parts of us in his hands, with women’s pubic hair, drunk, he danced and the crowd gathered there before him was all the worse for cheering and laughing along with him.”

We talked about all this in class, deeply, and in subdued tones. I sensed, and I’m sure others did as well, a needed humility and awakening in those conversations. This was heartening to witness. Having worked with Joanna Macy, and her systems thinking and deep ecology, I have long practiced and learned the transformative power of grieving and believe that lasting true change only comes through the door of feeling and being with a broken heart.

We also shared moments of silence for the Native people, engaged in personal breakout conversations about how it was to read this book at the most personal level, and finally, I asked everyone to think on this question: What did I learn from the novel There There by Tommy Orange? (Below, I posted comments from the different classes, and my own thoughts).

Literary Inquiry

Thinking about this book from the perspective of the conventions, below are some notes from class.

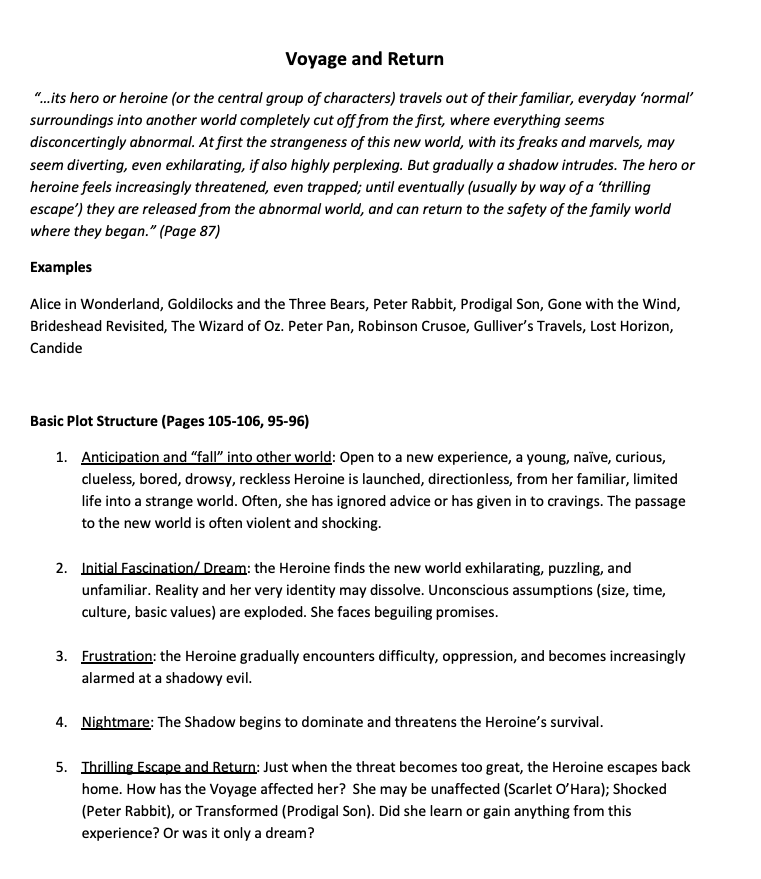

- If we considered Tony Loneman as our hero, Voyage and Return from the Booker model worked, and the handout is below:

Tony Loneman falls into the “rabbit hole” of the Drome (Fetal Alcohol Syndrome) when it is brought to his attention by a classmate, and then at the end emerges “home” at his pre-Drome self. He is “out of the hole” of that self-identification and transformed.

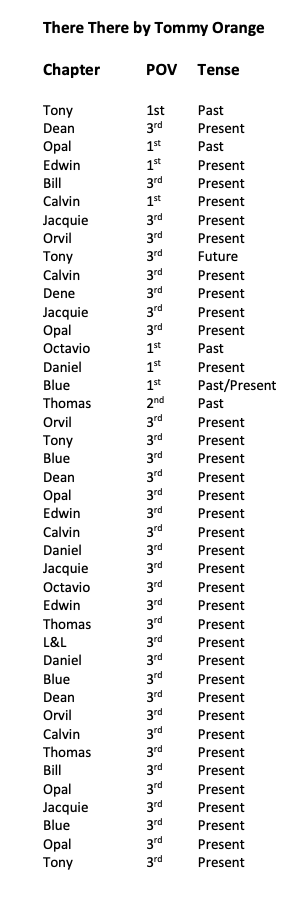

2. Tommy Orange used nearly every POV and tense possible, teaching us to not be hostage to conventions of voice, and here is that breakdown chapter by chapter.

3. Structurally, Orange hit two of the plot points on target. There was also a clear hook, inciting incident, and plot point one (PP1), all laid out in Tony’s opening chapter but the impressive backstory to solidify the inciting incident and PP1 happens in the first Calvin Johnson chapter, which falls exactly a quarter of the way through There, There. Tony hits his own mid-point (the antagonist overpowering the hero into stunned helplessness), when at page 143 he asks himself, “how he had wound up here…” after tossing two socks of bullets over a hedge where the powwow will play out.

Beyond Conventions: A Look at Native Structures

If I can jump ahead and answer my own question posed in class, Tommy Orange taught me this: When everything has been taken, even your life, there is more… there is always more.

Tony Loneman knew this in the final act of There There when seeing a Native kid in powwow regalia get shot. Tony begins to go hot and hard in that way that means he will be leaving the moment and not returning until later, only this time “…Tony means to stay, and he does. His vision brightens. He builds up to a run.” Pg. 286-87.

Tony rushes a gunman and takes him down, which then stops more bullets from killing more innocent people. In that moment, as Tony ends the gunman but also dies from being shot, he enters the realm of something greater than himself. This moment in There There is what I’ve taught this year as chiastic time, circular and flowing both forward and back. Tony Loneman arrives at a four-year-old version of himself, not going back but splitting time to enter himself pre-Drome and playing a bubble game with his grandma, asking, “What are we?” Then Tony continues down that path to playing a second game, this one with his Transformers and running out the plot line of battle, betrayal, and sacrifice. The Optimus Prime character in Tony’s childhood game says, “We were made to transform. So if you get a chance to die to save someone else, you take it. Every time.”

I mention my own learning from this book because it tips, rather nicely, into a necessary conversation about Native construction. This is from posting by AJ Eversol titled The Joy of Native Storytelling Structures. (Provided by a SIV writer. TY Cevia): The themes of Native stories are as varied as any culture’s, but they fall outside western expectations when they focus on broader concepts rather than narrow ones. Typically, our stories provide universal interpretations of the world around us and give commentary on our possible place within it… In my family, we freeze our walks in the woods just to admire a bright red cardinal perched atop a branch. In Cherokee culture, this bird is a messenger. Seeing it perched signals to us that we should stop and listen. Sometimes we need to be humbled by acknowledging the giant world around us. This means that we slow down the storytelling. We take pregnant pauses. The point of the story is to discover the world around us and listen to what it says to us, to let it tell us our story and where we fit into the world around us.

Eversol is telling us that Native stories, not all, but many bring about transformation in the reader by the way the story is told…character growth isn’t the point. Reader growth is. And that is what I experienced in reading this book. I grew, artistically, personally, and as a teacher!

Eversol continues: We were assimilated by force. It wasn’t a willing thing to abandon the familiarity of our story structure. Our ancestors were thrust into western ideology and away from our own. It can be difficult for Native writers to embrace a traditional Native story structure because we are so accustomed to adapting our stories for different audiences.

Choosing to not adapt that structure and instead to claim it with planted feet is an active way to participate in decolonization and reclaim what is ours…

Did Tommy Orange refuse to adapt his structure in There There? Or was it a mix? A little from the classic forms/conventions, a little from Native structures? I don’t know. I almost don’t want to know because I trust that we, in community, engaged with the material in the deepest way possible, placing the work at center, and leaving the actual writer alone.

Looking to the future

There There is a book of lamentation, of struggle, of setting the record straight, and of gifts all at the same time. I am hopeful that our time with this important book leads us through grieving, into making necessary amends, conditioned forgiveness, and finally, finally, the partnership of brothers and sisters who look toward a better future.

Perhaps this is a bit of my own magical thinking, the utopian who seeks that which lays over the horizon, but I want to see our tomorrow that way. I want to hope. And for all of this and more, I bow to Tommy Orange. Thank you, Sir, for this fine and important book.

If you haven’t read it yet, get it, read it and please, add a comment on what you learned from the novel, There There by Tommy Orange.

Writer Insights and Comments:

From Cevia: I was struck by the complexity and diversity of Native American identity and the far-reaching effects of generational trauma.

From Taylor S: I couldn’t believe how close he made me feel to each of the characters. Especially for a group of people who are often talked about so separately. I felt like I was able to see bits of myself in all the characters (despite not being a bat-killing alcoholic custodian). He really showed me how you can invite people into a story and make them feel part of it.

From Brenda: I learned how to connect the story through the interweaving of characters. I also felt like I was being told a truth that I needed to hear. Last, I find myself hearing the Indigenous voice in a way I had not heard it before. What a gift.

From Yushin: I read a short poem by Kim Stafford this morning. The last part goes: “From your hoard of reticence/your burrowed think, your/dream in chains, your/collared love on leash—make your secrets sing. Put them into ink. I learned what it looks like to make even your darkest secrets and ugliest trauma sing.

From Ellee: There There humanized the modern devastation of the Native communities. It revealed the realities of historical trauma and how it manifests for future generations. The book was a bridge.

From Camille: There There made me come full circle with the human need to tell a story. I loved that his writing was so very honest even as it presented difficult topics such as teen pregnancy, addiction. There There is a gut wrenching reality that we all have a story to tell whether it’s pretty or sometimes ugly, it is why we are here. So hard to ponder what we have done to Native peoples. We need to learn about it and continue to revisit the tragedy.

From Patricia: There There haunts its readers. The past running into present is not something I’ve ever felt so clearly.