Writing Workshop: The Attack Sentence, Plot, and the Underlying Message of an Epic

A love story, an adventure, and an epic of the frontier, Larry McMurtry’s Pulitzer Prize-winning classic, Lonesome Dove, the third book in the Lonesome Dove tetralogy, is the grandest novel ever written about the last defiant wilderness of America.

Journey to the dusty little Texas town of Lonesome Dove and meet an unforgettable assortment of heroes and outlaws, whores and ladies, Indians and settlers. Richly authentic, beautifully written, always dramatic, Lonesome Dove is a book to make us laugh, weep, dream, and remember. ~ Goodreads

When you think about Lonesome Dove, you might immediately think about the mini-series with Robert Duvall and Tommy Lee Jones that attempted to recreate this eight hundred and fifty seven page Pulitzer Prize winner in five puny episodes. In this writing workshop, I urge you to think again. Lonesome Dove is a remarkable read.

The biggest obstacle to reading this epic has to do with our hunger for speed reads and tight storylines. Thanks TV, movies, and the internet. Try to slow down and be drawn into this world. It will be worth it. Or, if you can’t slow down, listen instead. Audible has a wonderful version.

Another challenge is the sheer number of characters, both vast and intimidating, but again…hold steady. McMurtry is a gifted storyteller and you won’t flounder (founder) for long. Yes, you might be lost in a name soup for a while but some of the writers at the Studio printed out a list of the characters, which is easy to find online. Like this one over at Wikipedia.

Writing Workshop Tip #1:The Attack Sentence

There is just so much in Lonesome Dove to study and steal for the hungry writer. You could take weeks isolating and studying McMurtry’s management of multiple characters, points of view, and story arcs. Or you could hone in on his descriptions of people and place. Or, you could analyze his dialogue.

We, at the Studio, honed in on “The Attack Sentence” as part of a year long conversation on consecution which was taught based on this essay by Jason Lucarelli:

Examine your opening sentence (attack sentence/Lish) which should…create interest and draw readers into the world of the story while also announcing, in some way, the essential desire, topic or structure of the story.

“You take the initial sentence, your object, and you extrude and extrude, unpack and unpack, reflect and reflect, all in ways thematically and formally akin to the ways in the attack, the opening, the initial sentence” (Lish Notes, 41).

…(the attack sentence) starts the riff of the narrative, then what follows pushes the narrative forward through a kind of narrative logic that says whatever comes to the page must be a function of what is already present on the page.

Does McMurtry have an “attack sentence?” If yes, how does he “extrude and extrude, unpack and unpack, reflect and reflect, in all ways thematically and formally akin?”

Let’s take a look:

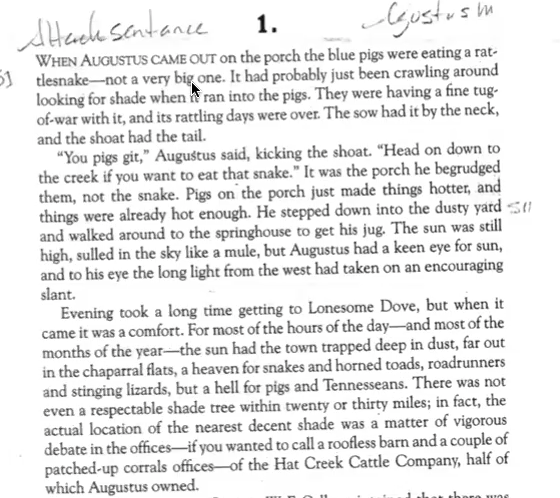

This is the opening of Lonesome Dove and where one can usually look for the attack sentence. In this case, McMurtry does have one: “When Augustus came out on the porch the blue pigs were eating a rattlesnake–not a very big one.”

The image is not just literal but figurative in that a rattle snake isn’t necessarily something you’d expect a pig to eat and live to tell the tale but they do. This eating, and conquering, of a lethal creature (the rattler) is also a metaphor for the entirety of this book in that what doesn’t seem possible becomes possible-Like the conquering of the native people and the securing of the land turns out to be a bad idea because those who occupy the land, in the name of Americans, are snake-like and reptilian-brained, greedy and brutal. The snake and pigs are stand-ins for Cal and Gus too, who will argue about many things over the course of this book but start their argument here with the pigs, Cal saying they are stupid and Augustus insisting they are smart.

In fact, while you might be questioning the need for the pigs in the story at all, it turns out that this pair of pigs will go on this journey and survive the entire time, overcoming obstacles that will kill many of the men.

For the next several paragraphs, McMurtry continues to describe the pigs and the snake, and snakes, in general, and is always progressing this element of the story while adding more and more information for the reader about these people and the situation that defines their struggle.

You could go into this book, chapter by chapter and do the same thing I’ve done here. Check out his opening sentence, track the progress of the primary image, and you’re on your way to seeing an attack sentence in action and then learning how to apply it to your own work.

Tip #2: Plot

If one cuts more deeply, the lonesome dove is Newt, a lonely teenager who is the unacknowledged son of Captain Cal and a kindly whore named Maggie, who is now dead. So the central theme of the novel is not the stocking of Montana (with cattle) but unacknowledged paternity. ~ Larry McMurtry

When trying to understand plot, the thing to pay attention to is the one who begins and ends the story. This is usually the primary protagonist, or hero (and they don’t necessarily need to be heroic). Once you’ve found that person, you can begin your analysis of plot. Some people slide past this hard work of sussing out plot by leaning into the author’s thoughts about his or her hero, and trust that the author knows who that person is. While McMurtry wrote the lonesome dove in his book was Newt, this isn’t a structure/plot conversation as much as a thematic one.

Since the writer is usually the least reliable source for understanding his own structure or plot, largely because of blindspots in the writers consciousness and understanding but a deeper study of McMurtry’s thinking reveals that Lonesome Dove was shaped along the lines of Cervante’s Don Quixote.

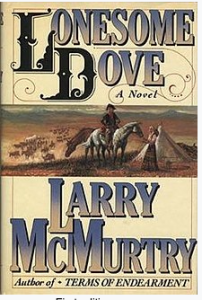

Now we are getting closer to understanding plot because the man, Cal, who is in the book from the beginning to the end, emerges as our hero in the shape of Don Quixote who was a hero in a quest plot that goes the distance. But Cal isn’t Don Quixote, who wins true self-knowledge and see’s whole. In the end, Cal is a hero who spirals further and further down the tragic plot. Here is the handout for that plot and a six minute clip of the conversation in SII. Click here. Warning, there are a few swear words. I get a little passionate about plot!

Tip #3: The Underlying Message of Lonesome Dove

On surface, this is a story about a sweeping and intense time of American history that immerses the open, humble and willing reader in the complexity of the lives of these men and women. Below the surface Lonesome Dove is an examination of conscience on the part of two Rangers tasked to clear the West of the native people for the coming pioneers. While Call and Gus acted as arms of the government’s agenda both lost their souls in that work. Gus admits it. Call denies it. In the end, both men fall into more and more ruin which–as a great story always proves out–is price they must pay for conquering the wrong people for the wrong reason.

One student in the writing workshop was offended by what was called a “glorification of the Rangers,” didn’t read this book. This position is common for those who insist on filtering literature through dearly held positions and trending political agendas. Currently, we live in a era of self-flagellation for the sins of our father’s and grandfather’s. Guilt, judgement and shame are the props being used to further this agenda.

Serious literature, work that stands the test of time, is classic and enduring. As part of that tradition, a well-wrought tragedy can never be a glorification of anything but rather is meant to show us ourselves. A classic tragedy is a testimony to the the futility, stupidity and ruination of an ego driven life.

Remember, that in the end, we are writer’s in this great tradition and to have any value as such, we are called to expand our thinking beyond what is popular in the moment. Reading Lonesome Dove is a great start on that journey. Good luck!