Learning from Without a Map by Meredith Hall – Writing Skills Course

(From Flight School: 11/27/22)

(From Flight School: 11/27/22)

This week, we’re going to look at Without a Map by Meredith Hall, a book thirty-six writers and I studied at the Studio for three weeks this fall.

The goal of this post is to share our process and conclusions.

To be clear, I’m not saying you should or shouldn’t read this book. I’m not endorsing it, nor am I shooing you away from it.

Instead, this is a journey of exploration…a way to think about a book you are reading that moves beyond judgments of good or bad, worthy or unworthy, right or wrong.

Let’s do it!

About the Book:

Meredith Hall grew up bonded to her insular New Hampshire community, comforted by the hallmarks of belonging: perfect attendance in Sunday school, classmates who seemed more like cousins, teachers who held her up as a model student, a mother who loved her unconditionally. Then, at sixteen, she became pregnant, and all at once those who had held her close and kept her safe turned their backs.

The same day in 1965 that Meredith was expelled from school, her mother told her “You can’t stay here.” Her father and stepmother reluctantly offered Meredith a cold sanctuary until she gave birth to the child she gave up for adoption. Then she was banned from her father’s home forever. For the next decade she wandered, lost to society and to herself. Slowly, Meredith began stitching together a life that encircled her silenced and invisible grief.

When he was twenty-one years old, Meredith’s lost son found her. She learned that he had grown up in gritty poverty with an abusive father—in her own father’s hometown. Their reunion was tender and turbulent, a renaissance. Meredith’s parents never asked for her forgiveness, yet as they aged, she offered them her love.

Without a Map charts an extraordinary journey in which loss and betrayal evolve into compassion and ultimately wisdom. ~ From Hall’s site page.

Memoir? Collection of Essays?

On the cover, we are told that this is a memoir, which by traditional definition, is “a nonfiction category strongly linked with the personal essay,” according to Brenda Miller and Susanna Paola, in the third edition of Tell it Slant. “Memoir comes from the French word for memory; to be a memoir, the writing must derive its energy, its narrative drive, from exploration of the past. Its lens may be a lifetime, or it may be a few hours.”

For those of us working on memoirs at this time, we have certain expectations, which include that if a book is called a memoir it will be a full-length story that presents a problem that is either resolved or not, by the final page, and that the memoirist will work the material in a manner similar to what we might read in a novel.

This expectation was the first dilemma surrounding our approach to this book because while there was a cohesive story for a while, there was also a sense that the various chapters did not quite mesh together. Again…no judgement. The writing was terrific, to be sure. Hall is a skilled wordsmith, but at times readers (myself included) felt…lost. “Where is she taking me,” many asked themselves. This sense of being lost created the following responses: To stop reading. To force through, keeping an open mind. To enjoy the disjointed construction as an example of what’s possible in the genre.

The construction Hall used was called out in a question-and-answer interview at the back of the book:

Interviewer: You wrote a fairly non-linear manuscript—you often jump back and forth in time…This seems to have confused some readers, and it’s something that other readers have found very appealing.

Meredith: Yes, I was not aware of moving in time. I wrote about my mother. About my baby. About my town. About my pregnancy. About my father. I did virtually no revision, simply wrote. One day, I felt I was done. I printed it all out and spread the pieces on my bed in my apartment. I made a list of what I had in front of me and realized that I should organize the pieces chronologically for clarity.

Okay. So…now we have a clue about what Hall intended. “I did virtually no revision.” And, “One day, I felt…done.” And, I organized the pieces chronologically…”

This makes sense.

A bit of further exploration took our inquiry to the front cover page, which lists the category of this book for shelving and sales purposes to include: childhood and youth, 21st-century biography, homes and haunts—Maine, and Maine—social life and customs—21st century.

Conclusion: Memoir seems to have been used more as a subtitle, but not as an official category.

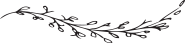

A little further down, we found a listing of the following credits, meaning that several chapters of the book had already been published, as stand-alone essays, in numerous publications:

Excerpt from Without a Map by Meredith Hall

This info is most helpful for the befuddled reader because we can see that we have here is more of a collection of essays.

So the question now is…can it be both a memoir and a collection?

Yes.

And no.

And yes.

That’s the crazy thing about publishing. They can do whatever they want. It is all “art” and today’s memoir can be tomorrow’s collection.

One additional consideration is about the time that this book was released: 2007. My deduction about this time is that this was the “early days” of memoir in its current incarnation and “anything goes” was the rule. Memoirs coming out aren’t quite as disjointed or experimental, but that doesn’t mean they can’t be. In fact, the moment you feel you get a fix on what the rules are…they change. Publishing and those working in that business makes up the rules as they go.

Structure? Plot? Value?

No matter what you call a book…memoir, collection, novel…it is still possible to suss out the structure, plot and value. And doing so gives you more power when understanding your own work.

(To read more on this teaching, which I called The Secret Sauce, go check out Flying Lesson #7)

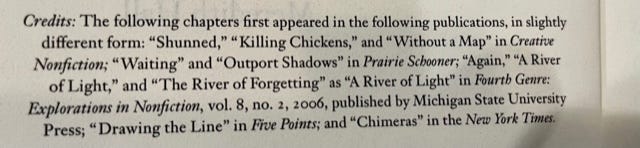

To talk about structure, we first determine the protagonist who, in this book, is Meredith.

Based on our discussion, we believe the hook is that she is pregnant in a community that is supposed to support her, has supported her until….

Meredith isn’t only abandoned by her community, she is abandoned by her mother, which then becomes the first plot point. Remember that the hero is on a particular course, then something happens to alter that course and the hero must embark on a new journey. For Meredith, the new journey launches with her mother saying: “You can’t stay here,” effectively kicking Meredith out of her childhood home.

On this new journey, Meredith goes to live with her father, and during her pregnancy tries to settle into this new home with its new routines. In the ways she fit at home with her mother, she is trying to do the same (1st level response) only she is required to stay out of sight.

At the midpoint, which happens off stage, Meredith has her baby and returns to her mother’s home, where her mother shows her sympathy and a desire to get Meredith back on track with her life, but now it is Meredith who makes the decision to leave. In an interesting reversal and in fury toward her mother, Meredith exiles herself.

First, she goes to an alternative boarding school (arranged by her mother) and then, step by step, enters into a life in which she becomes increasingly exiled.

Near the climactic action, she is traveling abroad—alone. Near the end of this, the 2nd level response) she is nearly penniless, homeless, and selling most of her clothing until, in Syria, she is down to nothing but a sleeping bag and underwear. This is the moment of truth. Die? Or change? Coming across a group of women working in the fields, their babies slung to their backs and hips, Meredith is given a cup of breast milk and she drinks. And her exile is now complete. You might call this the climactic action because she seems to have made a decision, like the one foisted on her in the inciting incident, but like the mid-point, it happens off stage. The reader has to fill in the gaps, which frankly, isn’t hard to do based on what Hall gives us of the story.

In later chapters, Meredith returns to the US, fashions a life for herself, marries, has two children, gets enough education to write and teach (take care of herself), and eventually is found by the child she had back when originally exiled. Once more, Meredith surges into this relationship willingly, embracing her forsaken child and fashioning a relationship with him and his adoptive parents. Her greatest fear, as stated at the beginning of the book, is that she will be exiled again and so she does all she can not to be exiled by the son she gave up, and those she loves. While living in fear, she is within a new collective of her own children and the story ends with them helping her build her own home…which is far away from the world (self-exile). But okay. This is her life.

Even now, I talk too much and too loud, claiming ground, afraid that I will disappear from this life, too, from this time of being mother and teacher and friend. That It—everything I care about, that I believe in, that defines and reassures me—will be wrenched from me again.

Without a Map by Meredith Hall

So, what is the plot?

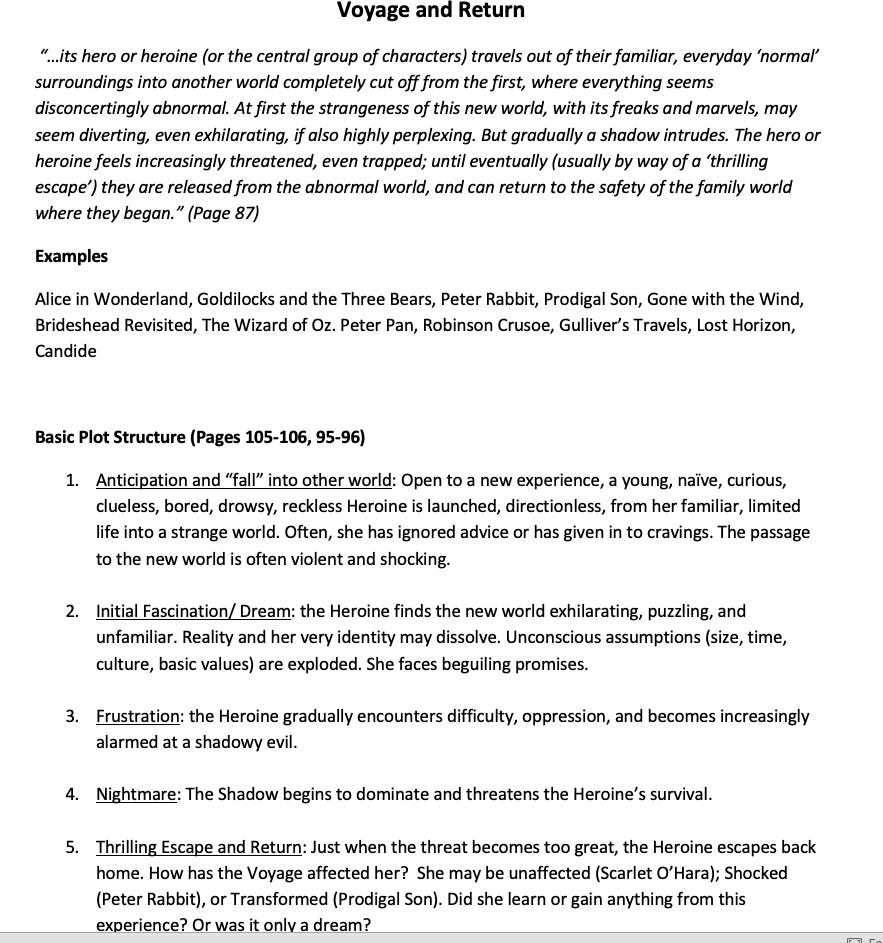

The answer, we concluded, is Voyage and Return, meaning Meredith was dropped out of her known/knowable world and into one where a girl is shunned and never, not ever, allowed back. She lives in this world for a while, exiling herself for a long time, and then returns changed in that “home” cannot be taken from her…not really…home is wherever she finds herself. And in this new awareness, she now fashions a new life for herself while carrying…always…an underlying fear that it will all be taken away too. In the end, she is both changed but also trapped in a way, in the core wound of being shunned.

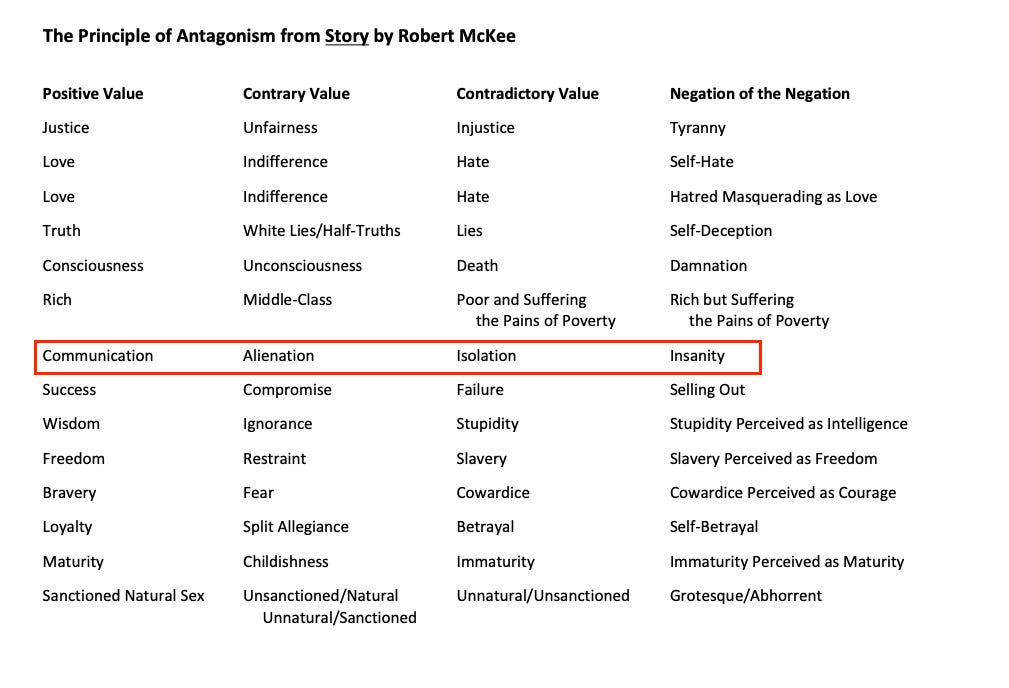

This brings us to the question of value…and we turn to Story by Robert McKee for our trusty chart that doesn’t necessarily provide all the values that humans hold dear, but is a good start.

A bit of discussion about the structure and plot, and presto, pow, we have our value which is communication.

We know this is true because Meredith, at every turn, is communicating with her family, her birth son and herself throughout the story. She “lives in her head,” she writes at one point but this is more communication. Self communication. Meredith values clear, honest, and understandable communication with herself, those who will listen, and to those who refuse to listen, she continues to try to communicate.

Finally, throughout the primary story line (that of being in exile) she goes through the various antagonistic stages aligned with communication, including being alienated, isolated, and even going slightly mad while traveling abroad, selling her clothes and wandering like a nomad.

In Sum:

From Tell it Slant: “Richard Hoffman, in his essay titled Backtalk, defends the surge of memoir as a corrective to a culture that has accepted the verb to spin to mean deliberate distortion of our news.”

The ascendance of memoir…may be a kind of cultural corrective to the sheer amount of fictional distortion that has accumulated in [our] society.

I find this suggestion fascinating and more so in the examination of Without a Map. Even in the presentation of this book as a memoir, again listed in the subtitle and not in the category listing, and not even by the writer herself, who basically didn’t write a memoir as much as several shorts, we see this fictional distortion. This “spin.” What is it we are reading? What are the rules? What can we trust? Understand?

Big questions. Difficult to answer as well.

Perhaps the very argument Hoffman makes can help point to why I study books in this manner; asking questions rather than accepting marketing copy or endorsements. Perhaps all this questioning enables me, and those who study with me to pierce the bubble of spin and fictional distortion so I can see…truly see…for myself what is going on. There is power in such seeing, thinking, questioning. It is the power that, as storytellers, we must seize otherwise we are participants in this “spin” and distortion meaning we are being “spun.”

I hope this conversation has inspired you to think more deeply, and should you read Without a Map, please, post a comment. I’d like to hear your take.

Thanks for sharing!