Best Writing Tips for Classic Stories That Miss the Mark

We dance around in a ring and suppose; but the secret sits in the middle and knows.

~ Robert Frost

Out here among the trees and wide open sky and the endless chatter of birds nesting, I’ve been thinking about the way we have come to accept the simple conclusions offered in a lot of our best stories. I’m talking about easy endings like the girl gets the guy or the other way around. Fame is achieved. A house purchased. Or the hero gets rich. These endings result in “egoic satisfactions” and while it is important to have our needs met, many believe that story is meant to go a step further. Story is a device of evolution.

Out here among the trees and wide open sky and the endless chatter of birds nesting, I’ve been thinking about the way we have come to accept the simple conclusions offered in a lot of our best stories. I’m talking about easy endings like the girl gets the guy or the other way around. Fame is achieved. A house purchased. Or the hero gets rich. These endings result in “egoic satisfactions” and while it is important to have our needs met, many believe that story is meant to go a step further. Story is a device of evolution.

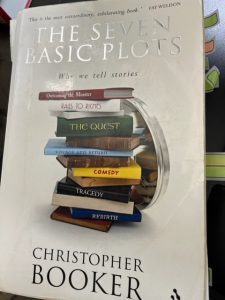

In Part III of The Seven Basic Plots, Why we tell stories, Christopher Booker provides a list of books and movies that he says have missed the mark by dropping into egoic satisfactions, or what he also calls sentimentality. I’ve gone through and reduced his list into a handout that you are welcome to print by clicking here (make sure hit to download). I’ve referenced pages numbers as well.

A Few Examples & Booker’s reasoning why:

Frankenstein by Mary Shelley (1816) – Why: This Overcoming the Monster plot turns everything upside down with a hero who is dark and a monster who is light; and ends with the hero being overcome by the monster, rather than the other way around. The scenes and details emerge from Shelley’s own life with her husband, who she eloped with two years prior to writing this book. Shelley (the husband), found himself violently at odds with society. With dreams of revolution, overthrowing the established order, and his horror at the notion of a cruel, patriarchal God, Shelley was at war with the world of “Father.” His chaotic love life showed him equally at sea, having eloped with first wife, Harriet, then getting involved with two women at the same time before casting them both off and then eloping with Mary. MORE: pg. 357

Moby Dick by Hermann Melville (1851) – Why: The hero Ahab—an embodiment of the dark, heartless, all-consuming egoist—is the true monster. Ishmael, the lone survivor, like the hero of a Voyage and Return plot, returns unchanged. He remains as he was in the beginning—an orphan. He is the same the solitary, uninformed child he was at the beginning.

Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger (1951) – Why: Holden had a prolonged nervous breakdown. From the moment of his expulsion into the ‘other world’ he never managed to return to normality. Perhaps, like the novel’s reclusive author who, after writing two more books, shut himself away from the world for years without producing another book.

Star Wars (1977) – Why: When the hero, Luke Skywalker, and his companions penetrate the dark labyrinth of the Death Star to rescue the heroine, Princess Leia, they succeed in freeing her, but in doing so leave her captor, Darth Vader, still alive and in control of his dark kingdom. The anima can only be properly liberated at the moment the monster is finally overcome. It is precisely because the shadow has been eliminated that she can finally emerge into the light. An equally telling aberration appears right at the end of the film when, in the great hall of the Rebel Alliance, we see Luke and Hans Solo walking up through a cheering crowd to be decorated for their bravery. They are like boys walking up in front of their classmates to receive the approbation of their teacher or even “Mother.” In fact, Leia is the next best thing as “the sister” of the hero, meaning there is never a balanced union between the masculine and feminine. The image of these two male heroes standing together, side by side, is not the archetype of the masculine and feminine, but focuses on two men emotionally bonded in friendship by their adventures as seen in The Last of the Mohican’s, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Casablanca. This is a profoundly important aspect of American society, which carried so much unconscious emotional bruising from the way it was originally forged; from the rebellious desire to escape from the oppressively ‘grown up’ old world of Europe, and from the psychological one-sidedness of the struggle to impose the white man’s will on the vast natural wilderness of the “New World” and the original inhabitants who lived on the land. All this has engendered in America culture an endemic immaturity which we see reflected throughout its history, not just in the all pervasive sentimentality of Broadway musicals and the celluloid dreams of Hollywood, but also in the stories of Melville, Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Norman Mailer, JD Salinger, Philip Roth and John Updike. It is this which helps to explain the remarkable fact that so few stories conceived in America over the past two centuries have ever managed to resolve in an unambiguous image of the fully mature, fully realized self.

Star Wars (1977) – Why: When the hero, Luke Skywalker, and his companions penetrate the dark labyrinth of the Death Star to rescue the heroine, Princess Leia, they succeed in freeing her, but in doing so leave her captor, Darth Vader, still alive and in control of his dark kingdom. The anima can only be properly liberated at the moment the monster is finally overcome. It is precisely because the shadow has been eliminated that she can finally emerge into the light. An equally telling aberration appears right at the end of the film when, in the great hall of the Rebel Alliance, we see Luke and Hans Solo walking up through a cheering crowd to be decorated for their bravery. They are like boys walking up in front of their classmates to receive the approbation of their teacher or even “Mother.” In fact, Leia is the next best thing as “the sister” of the hero, meaning there is never a balanced union between the masculine and feminine. The image of these two male heroes standing together, side by side, is not the archetype of the masculine and feminine, but focuses on two men emotionally bonded in friendship by their adventures as seen in The Last of the Mohican’s, The Adventures of Tom Sawyer, Casablanca. This is a profoundly important aspect of American society, which carried so much unconscious emotional bruising from the way it was originally forged; from the rebellious desire to escape from the oppressively ‘grown up’ old world of Europe, and from the psychological one-sidedness of the struggle to impose the white man’s will on the vast natural wilderness of the “New World” and the original inhabitants who lived on the land. All this has engendered in America culture an endemic immaturity which we see reflected throughout its history, not just in the all pervasive sentimentality of Broadway musicals and the celluloid dreams of Hollywood, but also in the stories of Melville, Henry James, Ernest Hemingway, Scott Fitzgerald, Norman Mailer, JD Salinger, Philip Roth and John Updike. It is this which helps to explain the remarkable fact that so few stories conceived in America over the past two centuries have ever managed to resolve in an unambiguous image of the fully mature, fully realized self.

You can agree or disagree with Booker’s assessment, and I encourage you do to so in the comment section. What do you think? Are these books going the distance? Are they satisfying? Let us know your thoughts.