Analyzing “The House of Spirits”: Writing Workshops Near You

“If I just show up, and I work and work, there is a moment, a magical moment, at some point, when it gives.” ~ Isabele Allende

Summary: Chilean writer Isabel Allende’s classic novel is both a symbolic family saga and the story of an unnamed Latin American country’s turbulent history. Allende constructs a spirit-ridden world and fills it with colorful and all-too-human inhabitants. The Trueba family’s passions, struggles, and secrets span three generations and a century of violent change, culminating in a crisis that brings the proud and tyrannical patriarch and his beloved granddaughter to opposite sides of the barricades. Against a backdrop of revolution and counterrevolution, Allende brings to life a family whose private bonds of love and hatred are more complex and enduring than the political allegiances that set them at odds. (From the publisher.)

Jennifer’s Take: Some books come along and I struggle to do my “teacherly” work because they hit too deep. The House of Spirits was one of those.

Yes, the writing is solid, the craft clear, the passion unquestionable, and one cannot deny Allende has enjoyed commendable success…but…when a writer takes me on a 350+ page journey to arrive at a bottom line that rape begets rape down the generations without end, I’m a little…peeved.

“…and perhaps forty years from now my grandson will knock Garcia’s granddaughter down among the rushes, and so on down through the centuries in an unending tale of sorrow, blood, and love.” ~ The House of Spirits

That a writer calls generational rape “love” is another thing that makes me shake my head. No. Just no.

In reading this book, I was taken to Know My Name by Channel Miller who did the same thing, writing several hundred pages of a stunning outlay of abuse; first by Brock Turner, then by the judicial system, and finally in the press. As Miller writes her book, Trump was elected and hearings were held where prominent women testified to sexual violence only to have their predators placed in high seats of power. After reporting all this horror, Miller still wrote: “Every generation, we get a little more free,” and “it’s getting better.”

Honestly, I wanted to tear my hair out.

It happens.

I realize, of course, that there is far more to Allende’s book, and her meaning and the evolution of the protag (Esteban) who becomes a better person in the end and yes, that’s all true and can be debated but honestly, it’s best I let another step in with her point of view. In the spirit of allowing others to teach for a bit, I turned to long-time Studio writer, April Streeter who put together her thoughts and what happened in translation, and over time, to her experience with this book. Enjoy.

How Reading The House of Spirits Changed My Life

How Reading The House of Spirits Changed My Life

by April Streeter ~ Studio II

At the age of twenty two, I spent a year at the Universidad Complutense in Madrid and was in love with the Spanish language where the most mundane of conversations sounded entrancing.

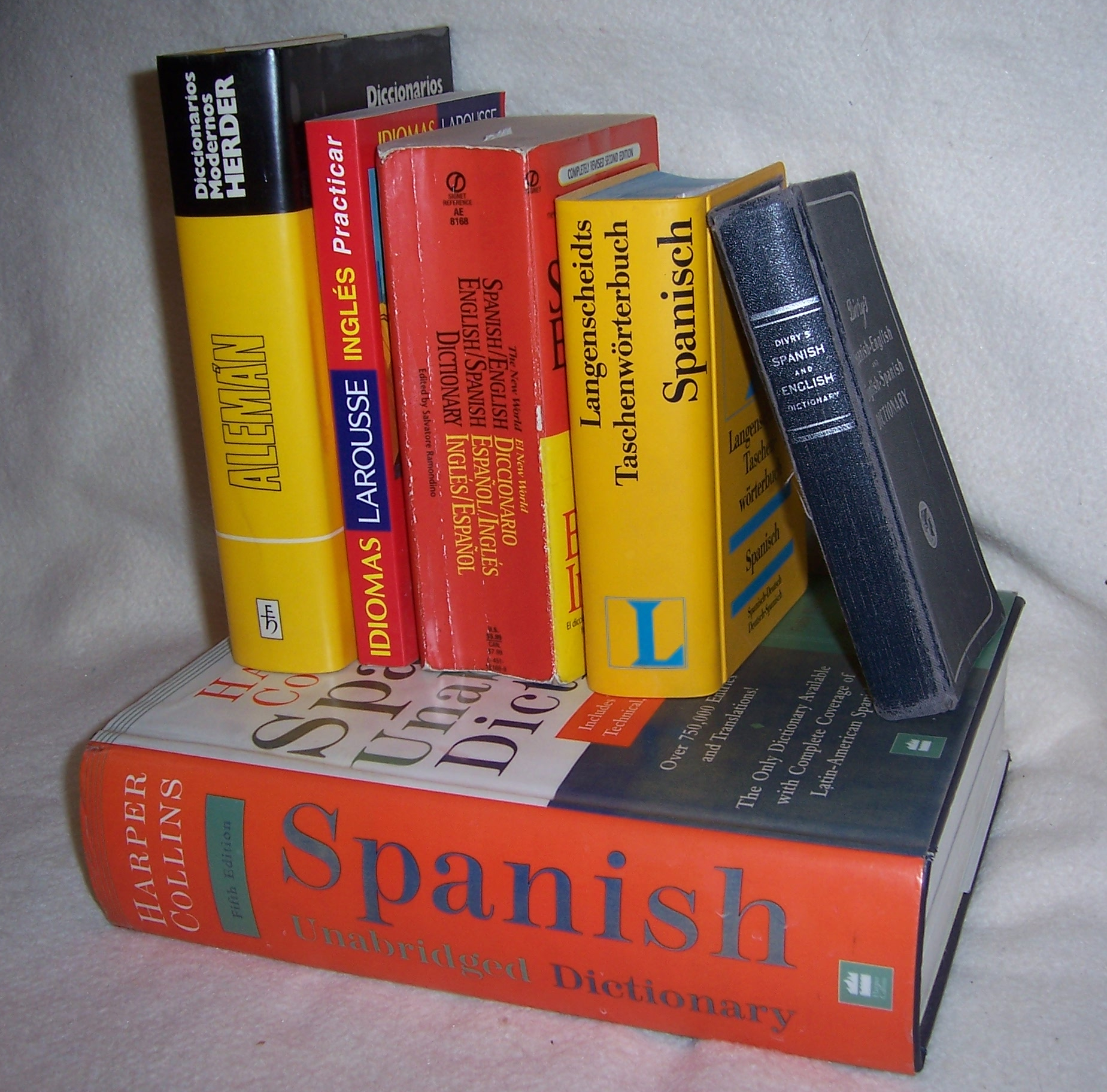

Once back in the U.S. I worked to keep the romance alive by reading in Spanish and read Cien Años de Soledad (One Hundred Years of Solitude) by Gabriel García Márquez. Each sentence was a labyrinth. My Spanish-English dictionary looked exhausted by the time I finished.

Undaunted, I next took on Isabel Allende’s La Casa de los Espíritus (The House of the Spirits), her most famous novel and a big bite of a book. With my battered dictionary at my side, I dove in.

Reading La Casa was falling into a heady, fantastical dreamscape. While in Cien años the characters were only intriguing, in Allende’s story the trio of strong female leads – Clara, Blanca, and Alba – captivated me. After a few chapters I forgot about the dictionary, resisted the need to understand every word, and let myself float along with the story. The outlandish and truly terrible violence and torture in La Casa de los Espíritus were blunted by the lull of the prose and the ongoing elements of magical realism. The language, the story, the characters – I was mesmerized.

I didn’t want the dream to end, or for Alba’s story to be over, but once done, I closed the thick paperback (much riffled and with a few tell-tale chocolate smears) and tucked it into a bookcase.

I tend to re-read my favorite books every few years. But in the case of La Casa de los Espíritus, I didn’t go back again until our scheduled Blackbird Studio II discussion. It had been nearly thirty-five years since that first read. I was a different person. A woman. A mother. Someone who had suffered betrayals of her own, and losses, and even what seemed unforgivable conflicts with others.

This time, I read The House of Spirits in English, too, and far more carefully, especially the first chapter. Here was Clara as a young girl sitting with her family and the ghostly Rosa, then Clara telling off the priest, chronicling the disappearance of her adventurous uncle and the arrival of the ‘utterly defenseless prisoner’ dog Barrabás. The magical realism was fully on display, as in the passage on Rosa’s death:

“…Rosa the beautiful had developed a chill. Nívea gave orders for Rosa to remain in bed, and Dr. Cuevas said that it was nothing serious and that she should be given sugared lemonade with a splash of liquor to bring down the fever…Nana woke up early as she always did…When she came to Rosa’s door, she stopped, gripped by a premonition. She entered without knocking, as she always did, and immediately noticed the scent of roses, even though they were not in season. This was how Nana understood that an inescapable disaster had occurred. She set the tray down carefully beside the bed and walked to the window. She opened the heavy drapes and let the pale morning sun into the room. Grief-stricken, she turned around and was not at all surprised to see Rosa lying dead on the bed, more beautiful than ever, her hair strikingly green, her skin the tone of new ivory, and her honey-gold eyes wide open, staring at the ceiling. Little Clara was at the foot of the bed observing her sister.” (pg. 23-23, Alfred A. Knopf edition, 1999)

Also clear from the first chapter were the themes of families and generational trauma, as well as the struggle between a corrupt patriarchy and the poor, with women lower than peasants and peasant women like Pancha, Esteban’s first sexual conquest, the most abject of all.

Allende kept the plot hot with the feverish romances between 1) Esteban and Clara, 2) Blanca and Pedro Tercero, and 3) Alba and Miguel, and she never stinted on lavish descriptions of love and love-making.

1) “He realized that Clara did not belong to him…He wanted far more than her body; he wanted control over that undefined and luminous material that lay within her and that escaped him even in those moments when she appeared to be dying of pleasure.” (pg. 83, Knopf)

2)“Blanca and Pedro Tercero slaked the accumulated hunger and thirst of the long months of silence and separation, rolling among the rocks and brush and moaning passionately. Afterward they sat embracing among the rushes of the riverbank.” (pg. 147, Knopf edition)

3) “One by one the lovers tried out all the abandoned rooms, and finally chose an improvised nest in the depths of the basement. They used her Uncle Nicolás’s books, the dishes, the boxes, the furniture, and the drapes of bygone days to arrange their astonishing nuptial chamber. In the center they created a bed by piling together several mattresses, which they covered with pieces of moth-eaten velvet…Alba invented irresistible techniques of seduction, and Miguel created new and marvelous ways of making love to her.” (pg. 280)

Still, the melodic beauty of Allende’s prose in Spanish could not be fully captured in the English translation. Spanish is the ultimate romance language with its plentiful soft consonants, long vowels, and easy rhyming ability.

For example:

For example:

“Esteban recurrió a la antigua cajita de píldoras homeopáticas para tranquilizarla, pero los sueños continuaran. ‘¡La tierra va a temblar!’ decía Clara…” (pg. 207, Vintage Español, 2015)

Vs.

“Esteban resorted to the old box of homeopathic pills to calm her down, but her nightmares continued. ‘There’s going to be an earthquake,’ Clara announced…” (pg. 136, Knopf)

Even without knowing Spanish, reading the words shows the difference in melody and you can listen to the difference here as well: Click to listen.

On this new read I also found the switching of point-of-view between Alba to Esteban to be jarring. I hadn’t even remembered Esteban’s first-person diary. If asked, I would have guessed that the tale was told by an omniscient narrator, i.e. the feminine force.

Yet, in English, I now concentrated on Esteban’s self-serving narration and the story became more tragic, more menacing.

I had also appreciated on the first go-round getting schooled in Allende’s interpretation of Chile’s history and the 1973 coup d’etat. But this time around, the violence, especially the recurring sexual violence, permeated the experience. The former spell delivered via melodic language was broken, the tragedy of generational trauma was inescapable.

The heinous male protagonists – Esteban and his namesake illegitimate grandson Esteban García – pursued their prey, seemingly unpunished for their misdeeds. All the women suffered unjustly under the men’s tyranny, from Esteban’s martyred sister Férula, to his abused wife Clara, to his granddaughter Alba who was tortured and raped.

At the book’s close, Alba emerges from her trauma determined to break ‘that terrible chain’ of hate. It is a personal and generational aspiration for her unborn daughter. We don’t know if she’s successful. In spite of that uncertainty, I came away from the book feeling hopeful.

In my twenties, I wasn’t yet awake to my own trauma and have to wonder if ideas of romance, and the melodic language of La Casa de los Espíritus, worked together to lull me ‘asleep’. On this most recent reading, I was fully aware of its dark undercurrents. Yet if The House of the Spirits is a tragedy in the Booker sense, with Esteban’s world destroyed by the malevolent forces unleashed by the coup, there is redemption and hope. Alba (in Spanish her name means ‘dawn’) is empowered to overcome her terrors. Through the experience of story, I’m able to believe that another world, in which trauma can be surmounted, is possible.

As a younger reader, plot, character, and style made me love books. Now I understand all of these elements are in service to creating a story that goes the distance. When characters are transformed by a story that does do that, I too am changed – enriched.

April Streeter is a longtime blogger and writer, the author of Women on Wheels: The Scandalous Untold Histories of Women on Bicycles (Microcosm, 2021). She co-edited Our Bodies, Our Bikes with Ellie Blue (Microcosm, 2015). She is a freelance journalist currently at work on her first novel, a fair-weather cyclist, and a bad knitter. To join April’s Monday through Friday 7:30 a.m. 30-minute morning yoga on Zoom, request a link from april.streeter@gmail.com.